LACEY TOWNSHIP, NJ — As New Jersey grapples with the fallout of Governor Phil Murphy’s struggling offshore wind energy plan, a look back at the state’s energy history reveals an even more audacious proposal: a floating nuclear power plant anchored miles off the Jersey Shore.

In the early 1970s, this radical idea captured the imagination of utility executives and sparked fierce debate, ultimately collapsing under financial pressures and public outcry. While Murphy’s wind ambitions have drawn criticism for high costs and delays, the offshore nuclear dream of yesteryear stands as a reminder that New Jersey’s energy experiments have long pushed boundaries.

The concept emerged in 1969, when Richard Eckert, an engineer at Public Service Electric and Gas Company (PSE&G), proposed a novel solution to the state’s growing energy demands. With suitable land-based sites for power plants dwindling, Eckert envisioned mass-producing nuclear reactors on floating platforms, towed to sea and moored off the coast. The plan, spearheaded by Offshore Power Systems (OPS), a joint venture between Westinghouse Electric and Tenneco’s Newport News Shipbuilding, aimed to build up to eight gigawatt-scale reactors, each capable of powering roughly 600,000 homes.

The first site, dubbed the Atlantic Generating Station, was slated for 2.8 miles off Little Egg Harbor Inlet, near Atlantic City.

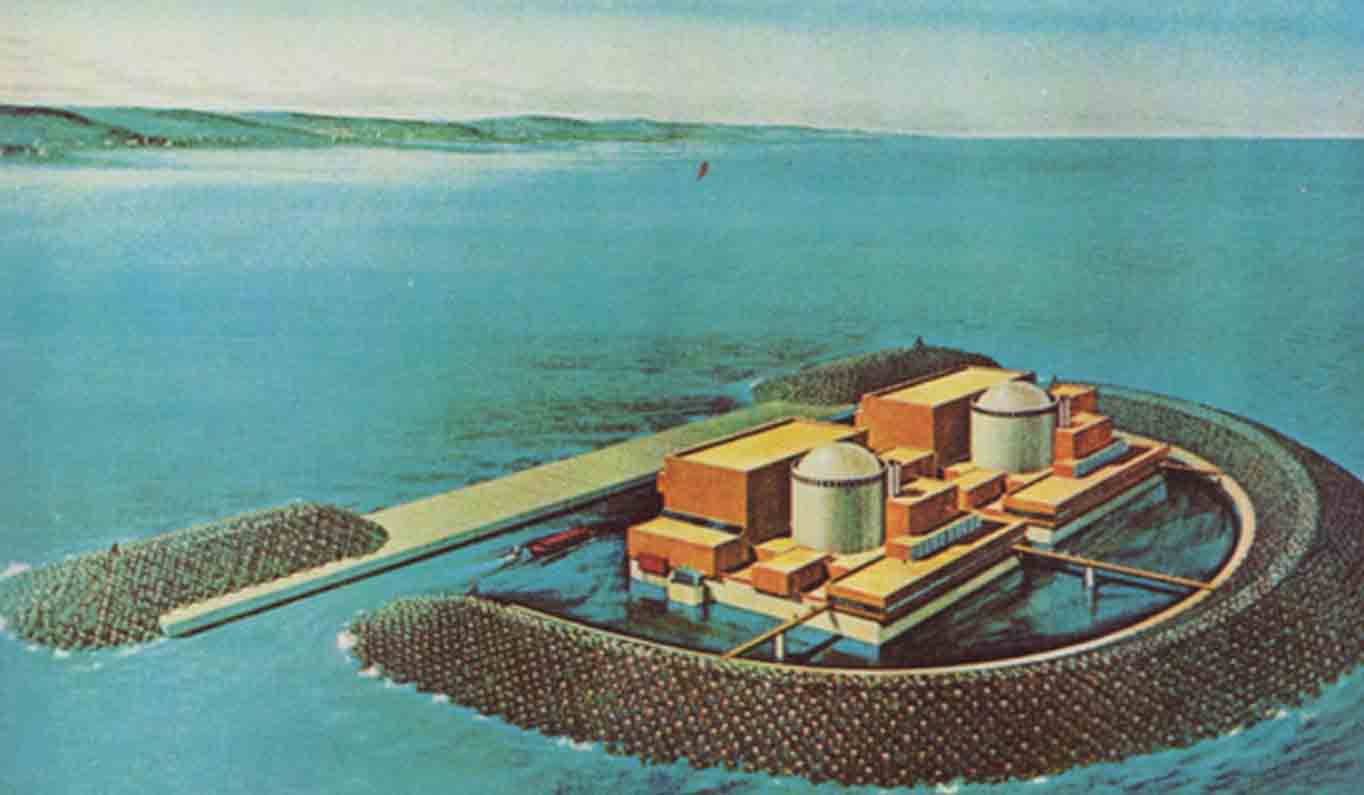

The pitch was bold: offshore nuclear plants would sidestep land-based opposition, tap abundant ocean water for cooling, and standardize reactor designs for cost efficiency. PSE&G ordered two 1,150-megawatt reactors in 1972, with plans for two more, targeting operation by the mid-1980s. The plants would sit on 400-foot steel platforms, protected by a massive breakwater of 18,000 concrete “dolosse” to withstand hurricanes and ship collisions.

Power would flow to shore via underwater cables, and the Jacksonville, Florida, production facility was projected to create 10,000 jobs. A $1.1 billion contract was signed aboard a yacht off the Jersey coast, symbolizing the project’s high-stakes ambition.

But the plan faced immediate skepticism. Environmentalists, local officials, and residents raised alarms about the risks of nuclear accidents, radioactive waste, and ecological damage to the Atlantic. Ralph Nader and the New Jersey Sierra Club joined the opposition, with critics like Joe Cury of Jacksonville protesting the safety of concentrating nuclear material at sea.

“Nuclear remains an unforgiving technology,” said R. William Potter, then-assistant deputy Public Advocate for New Jersey, reflecting on the fierce resistance. Concerns intensified after the 1973 oil crisis, which spiked costs and dampened electricity demand, undermining the project’s economic case.

By 1975, Tenneco withdrew from OPS, leaving Westinghouse to limp along. The 1976 presidential campaign of Jimmy Carter, who called for a moratorium on new nuclear plants, further eroded support. The final blow came after the 1979 Three Mile Island accident, which shattered public confidence in nuclear power. PSE&G canceled its contracts in 1978, and by 1982, despite a federal licensing board granting temporary approval, OPS had no buyers. The Jacksonville facility, which cost $125 million and featured the world’s largest crane, was dismantled, with the crane sold to China for a fraction of its value. The project was abandoned by 1990, leaving no trace of the “Atomic Atoll” off New Jersey’s coast.

Today, as Murphy’s offshore wind projects—like Ørsted’s canceled Ocean Wind—face scrutiny for costing billions and delivering little, the offshore nuclear saga offers perspective.

“It was an idea ahead of its time, but the risks were too great,” said Jeff Tittel, former director of the New Jersey Sierra Club. While wind turbines face supply chain woes and ratepayer burdens, the floating nuclear plan grappled with existential safety concerns and economic volatility.

Yet, with New Jersey’s Salem and Hope Creek nuclear plants still supplying 40% of the state’s electricity, some argue nuclear—on land—remains a more reliable path than wind.

Holtec International, which decommissioned the Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station in 2018, briefly revived the offshore nuclear concept in 2021, proposing a small modular reactor (SMR-160) at the Lacey Township site. The idea, backed by $147.5 million in federal funds, aimed to demonstrate next-generation nuclear technology but has not progressed, with critics citing sea-level rise risks. For now, New Jersey’s energy future remains tethered to land-based solutions and the uncertain promise of offshore wind.

As Trenton debates how to lower energy prices and meet clean energy goals, the offshore nuclear episode underscores a recurring lesson: bold ideas must balance ambition with practicality. Murphy’s wind plan may falter, but it’s not the first—or wildest—energy gamble New Jersey has seen.